Prisoner Of Pain

Jan. 26, 2006

(CBS) - The same judicial system that prosecuted Richard Paey for obtaining too much pain medication is now supplying him in prison with more than that amount to ease his tremendous pain.

60 Minutes correspondent Morley Safer reports on this case, in which an accident victim's quest to medicate his pain ran afoul of drug laws, this Sunday, Jan. 29 2006 at 7 p.m. ET/PT.

A long-ago car accident and failed spinal operation put Paey in such severe pain that only escalating amounts of opiate medication could relieve it.

"As I got worse, I developed a tolerance also with the medication and so I needed larger doses," says Paey, who describes the pain as burning in his legs. "It's an intense pain that, over time, will literally drive you to suicide."

Paey, who also suffers from multiple sclerosis, did try to commit suicide at one point.

After moving to Florida with his wife and children, Paey says doctors there were wary of prescribing the amounts of pills he needed as that would draw the attention of law enforcement. So he persuaded his longtime New Jersey doctor to continue prescribing his medication in the high amounts necessary for relief. The doctor agreed to fax and mail prescriptions and sometimes verified them to pharmacists.

Paey's frequent refills did draw attention and, before arresting him for drug trafficking, the Drug Enforcement Agency visited his New Jersey physician, Dr. Stephen Nurkiewicz. When confronted by agents about the number of pills Paey had purchased � 18,000 in two years � Nurkiewicz rescinded initial statements of support for his former patient and said Paey was forging prescriptions.

"In Richard Paey's room ... were the raw materials to make prescriptions," Florida State Prosecutor Scott Andringa says. "They found a lot of documents that suggested forging prescriptions."

They also found 60 empty bottles of pain relievers, some of which surveillance teams had watched Paey purchase. Andringa says there was no evidence that Paey was selling his drugs, "but it is a reasonable inference from the facts that he was selling them, because no person can consume all these pills."

Paey, confined to a wheelchair, is now serving 25 years in a Florida prison. A jury convicted him of 15 counts of prescription forgery, unlawful possession of a controlled substance, and drug trafficking. He had the choice of entering a guilty plea in exchange for no jail time but, for him, that was no choice, says Paey.

"Had I accepted a plea bargain and carried that conviction on my record, I would have found it near impossible to get any medication," he says. "I didn't want to plead guilty to something that I didn't do."

Paey denies selling his medication, saying he took and needed all 18,000 pills. This scenario � 25 pills a day � is plausible, says Dr. Russell Portnoy, chairman of the Department of Pain Medicine at New York�s Beth Israel Hospital.

Once acclimated to a drug, patients can regularly take what would be lethal doses to ordinary people, Portnoy says.

"It really sounds like society used a mallet to try to handle a problem that required a much more subtle approach," says Portnoy. "If they had taken this man who had engaged in behaviors that were unacceptable and treated it as a medical issue, it seems like this patient would have had better pain control and a functional life instead of being in prison."

Andringa disagrees. "This case is not about pain patients, it's just not. This case is about prescription fraud. We were very reasonable in this case. But once somebody says, 'I'm not going to accept a plea offer however reasonable it is �' "

Paey gets all the medication he needs now, in larger doses than he was taking before, from the state through a pump connected directly to his spine. He is appealing his conviction.

http://www.cbsnews.com/stories/2006/01/25/60minutes/main1238202.shtml

CBS News - USA

The Case Of

RICHARD PAEY

Drugs. While noble in concept it has been ignominious in application. Our

government has seemingly forgot the age old wisdom that in war, the first casualty

is always the truth.

Florida's attempt to expand the definition of drug trafficking so that

patients filling doctors prescriptions are now potential defendants. It doesn't

matter the patient had a medical need for the medication. If the state can show

your doctor acted outside the course of their professional practice then the

prescriptions are illegal. If the prescriptions are illegal and you have more

than 28 grams ( 50-70 pills ) that makes you a drug trafficker.

And that's what happened to Richard Paey, a 46 year old family man from

Pasco County, Florida. It didn't save him that he suffered from intractable pain

caused by multiple sclerosis and failed spine surgery. All that matter was the

State could convince a jury the prescriptions were illegal - even if the

illegality was caused by something Richard's doctor did or didn't do.

Here's what happened. To some its another example that the War on Drugs is

out-of-control. It may also help explain why "pain is woefully under treated in

Florida". The situation is so dire, Florida had to pass special legislation to

combat the fear of investigation that has caused some doctors to stop

treating pain patients (the "chilling effect").

For over 2 1/2 years Richard Paey received prescriptions from his doctor

that were filled at local pharmacies. In 1997 Pasco sheriffs started a secret

pharmacy surveillance program intended to identify people believed to be taking

excessive medication. In the mind of the sheriffs, excessive medication was

evidence of a potential crime. How they decided what was excessive, nobody knows,

it was a gut determination. Because the deputy believed Richard Paey took

excessive medication, police put him under surveillance - for 3 months. They

found nothing.

Undeterred by the lack of evidence sheriff's deputy's decided the doctor was

also a suspect. Because the doctor continued to authorize prescriptions the

sheriff felt they had to approach the doctor with that they called a "ruse"- an

intentional lie. They decided to tell the doctor his patient was selling the

medication and the doctor faced 25 years in prison for sending the

prescriptions to Florida.

What did the sheriff expect the doctor to say? With news he faced

prosecution (utter ruin) the doctor began to "back pedal". In what police acknowledged

was an incredible story, the doctor claimed he had been "lying" when he told

pharmacists he wrote the prescriptions. He didn't write them, he said, he didn't

know who wrote them, apparently. He had authorized them because he was

helping his patient. In short, when told he faced prosecution for writing the

prescriptions, he told a new story.

Police arrested Richard alleging the prescriptions were illegal because they

were not written by the doctor. The fact the doctor made the allegation only

after being told he faced prosecution, didn't matter. All that mattered was

they had someone to swear to the allegation.

Although the state originally alleged the doctor was duped into authorizing

prescriptions and lying to pharmacists the state did its own back pedaling

when the allegation was recanted by the doctor at trial. Ordinarily recanting an

allegation before the jury ends the trial, but not here. The state told the

jury they should convict regardless of what the doctor said in court. According

to the prosecutor, the prescriptions were illegal simply because they had been

written or issued 6 weeks after Richard's last medical exam. It was still

drug trafficking, the jury was told.

If you think the prosecution demonstrates the War on Drugs is

out-of-control, you won't be surprised by what the jury did during deliberation! When jurors

could not agree on a verdict, the persuasive jury foreman told the group it

was okay to vote for guilt because he, the jury foreman, knew the defendant

would only get probation. Unfortunately, the foreman was terribly wrong. The

judge had to impose the mandatory sentence of 25 years.

Today the defendant is housed in a prison infirmary awaiting his appeal.

Because he was convicted of drug trafficking, he could not be released pending

appeal - like murderers and rapists. He want directly to prison. The drug

trafficking statute contains harsh provisions intended to make convictions easier. It

did.

Has the War on Drugs gone too far, is it out of control? This case seemingly

says YES.

Did you know Floridians are suffering unnecessarily because many doctors are

afraid of police knocking on their door? According to Florida Hospice, even

terminally ill patients are being under treated, a situation attributed

directly to overzealous enforcement officers.

Did Florida have to adopt special legislation telling doctors its okay to

prescribe to pain patients; that large doses, even over the patients lifetime

may be necessary? Has the law alleviated doctor's fears or has the situation

gotten worse?

Can juries, should juries decide when your doctors prescriptions is illegal

because its "not written in the course of the doctors professional practice"?

If experts in medicine disagree on how much is excessive or whether 6 weeks

between visits is too long, how can a jury?

Would you want police to test your doctors courage using a "ruse"? Are the

officers overzealous in their pursuit of prosecutions?

What is drug trafficking if its not trafficking? Is trafficking filling an

prescription made "illegal" by some decision your doctor made?

What should be done to help ensure intractable pain patients can find

treatment?

Is the current Controlled Substance Act (1970) part of the problem? Did

mandatory minimums help in creating a fair, equitable sentence in Richard's case?

According to Richard's attorney, this is the first prosecution of a patient

for something his doctor did or didn't do. Was Richard a drug trafficker or a

victim?

PUNISHING PAIN

By John Tierney

July 19, 2005 - Zephyrhills, Fla.

When I visited Richard Paey here, it quickly became clear that he posed no menace to society in his new home, a high-security Florida state prison near Tampa, where he was serving a 25-year sentence. The fences, topped with razor wire, were more than enough to keep him from escaping because Mr. Paey relies on a wheelchair to get around.

Mr. Paey, who is 46, suffers from multiple sclerosis and chronic pain from an automobile accident two decades ago. It damaged his spinal cord and left him with sharp pains in his legs that got worse after a botched operation. One night he woke up convinced that the room was on fire.

"It felt like my legs were in a vat of molten steel," he told me. "I couldn't move them, and they were burning."

His wife, Linda, an optometrist, supported him and their three children as he tried to find an alternative to opiates. "At first I was mad at him for not being able to get better without the medicines," she said. "But when he's tried every kind of therapy they suggested and he's still curled up in a ball at night crying from pain, what else can he do but take more medicine?"

The problem was getting the medicine from doctors who are afraid of the federal and local crusades against painkillers. Mr. Paey managed to find a doctor willing to give him some relief, but it was a "vegetative dose," in his wife's words.

"It was enough for him to lay in bed," Mrs. Paey said. "But if he tried to sit through dinner or use the computer or go to the kids' recital, it would set off a crisis, and we'd be in the emergency room. We kept going back for more medicine because he wasn't getting enough."

As he took more pills, Mr. Paey came under surveillance by police officers who had been monitoring the prescriptions. Although they found no evidence that he'd sold any of the drugs, they raided his home and arrested him.

What followed was a legal saga pitting Mr. Paey against his longtime doctor (and a former friend of the Paeys), who denied at the trial that he had given Mr. Paey some of the prescriptions. Mr. Paey maintains that the doctor did approve the disputed prescriptions, and several pharmacists backed him up at the trial. Mr. Paey was convicted of forging prescriptions.

He was subject to a 25-year minimum penalty because he illegally possessed Percocet and other pills weighing more than 28 grams, enough to classify him as a drug trafficker under Florida's draconian law (which treats even a few dozen pain pills as the equivalent of a large stash of cocaine).

Scott Andringa, the prosecutor in the case, acknowledged that the 25-year mandatory penalty was harsh, but he said Mr. Paey was to blame for refusing a plea bargain that would have kept him out of jail.

Mr. Paey said he had refused the deal partly out of principle - "I didn't want to plead guilty to something that I didn't do" - and partly because he feared he'd be in pain the rest of his life because doctors would be afraid to write prescriptions for anyone with a drug conviction.

If you think that sounds paranoid, you haven't talked to other chronic-pain patients who've become victims of the government campaigns against prescription drugs. Whether these efforts have done any good is debatable (and a topic for another column), but the harm is clear to the millions of patients who aren't getting enough medicine for their pain.

Mr. Paey is merely the most outrageous example of the problem as he contemplates spending the rest of his life on a three-inch foam mattress on a steel prison bed. He told me he tried not to do anything to aggravate his condition because going to the emergency room required an excruciating four-hour trip sitting in a wheelchair with his arms and legs in chains.

The odd thing, he said, is that he's actually getting better medication than he did at the time of his arrest because the State of Florida is now supplying him with a morphine pump, which gives him more pain relief than the pills that triggered so much suspicion. The illogic struck him as utterly normal.

"We've become mad in our pursuit of drug-law violations," he said. "Generations to come will look back and scarcely believe what we've done to sick people."

E-mail: [email protected]

Richard Paey is a patient suffering from chronic pain who ran afoul of the law because of his efforts to get adequate medication. As reported by Florida's Weekly Planet on June 16, 2004 ( See "Mandatory Madness" below), ""You know when you have a toothache and the pain is so severe that you absolutely have to be seen immediately by a dentist?" says the man in the wheelchair. "Imagine if you had to grin and bear it for an undetermined period of time. You can't see straight. You think you'll pass out, and sometimes you do. And sometimes you pray you will."

Richard Paey, chronic pain patient, is describing how bad his body can hurt. He suffers from what is often called "failed back syndrome," an inoperable condition that has sentenced him to a life of pain that most of us hopefully will never have to comprehend. This is not his only sentence. On March 5, he was convicted of 15 counts of drug trafficking, obtaining a controlled substance by fraud and possession of a controlled substance, which earned him a mandatory minimum of 25 years in state prison and a $500,000 fine. This is what Richard Paey did -- or, more accurately, this is what a jury found Richard Paey ( pronounced "Pay" ) guilty of: fraudulently obtaining prescriptions of Percocet ( which contains the opiate oxycodone ) and Lortab ( which contains another opiate, hydrocodone ), each of which exceeded 28 grams. That's the magic number, 28 grams. Illegally possessing this amount gets you 25 years. It's the same mandatory minimum as 28 grams of heroin."

The Planet reported that "Paey is not doing time for just the opiates. Each of his Percocet pills contained 5 mg of oxycodone and 325 mg of acetaminophen ( Tylenol ). For sentencing purposes, though, the latter substance was weighed in as well. Eighty-five of his pills weighed 28 grams. If Paey were sentenced for just the oxycodone, he would've needed 5,600 Percocet tabs to earn a quarter-century behind bars. From January to March of '97, he bought 1,200 from area pharmacies. This inflated numbers game is just one perplexing fact in the strange and scary case of Richard Paey, 45, husband and father of three, convict. Consider also that Pasco sheriff's deputies surveilled him for weeks and never found any evidence that he sold a single pill. Yet the state attorney's office charged him with trafficking -- because it could. In Florida, you can be charged with trafficking certain drugs, oxycodone and hydrocodone included, without actually peddling them. You merely need to possess them illegally.

For its part, the State Attorney's Office in Pasco offered Paey several plea deals -- including, early on, house arrest and probation, then shorter prison terms. For various reasons, each deal went south. Some onlookers have characterized Paey as stubborn, saying that he put one foot in a prison cell by not jumping at the state's plea offers. Paey came close to cutting a deal several times, mostly at the urging of his wife, Linda, and his lawyer, but his heart wasn't in it. Paey has maintained all along that he did nothing criminal, that he was only medicating his own severe pain, which required large doses, and that his scripts -- written, faxed and phoned in by a doctor in New Jersey -- were legitimate. After one mistrial and another guilty verdict vacated by a judge who said Paey had not been competent to stand trial, he was convicted during a third proceeding. The jury was not permitted to know that Paey was facing a stiff mandatory minimum. One juror held out for acquittal but was eventually swayed toward a guilty vote when the jury foreman convinced him that the defendant would get only probation. The judge had no choice but to issue 25 years."

Richard Paey's case is truly tragic. As the Planet reported, "On Feb. 11, 1985, Richard Paey was driving on Philadelphia's pocked and frantic Schuylkill Expressway, on his way to class at the University of Pennsylvania law school, when he got into a wreck that sandwiched his car between two others. He went to the ER the next day. Directly after the accident, Paey began taking sizeable doses of opiate pain relievers. A few months later, he underwent his first back surgery, but that only offered about a year's worth of limited relief. In 1987, he signed on for another operation. Unbeknownst to him, he received a fusion procedure that included an experimental "pedicle screw" implant that had been turned down for approval by the FDA. The implants became the focus of a high-profile class action lawsuit that was covered by the TV show 20/20. Linda Paey said her husband never received a settlement because he got involved after a statute of limitations passed. His back went from bad to worse. He'd get spasms that would hamper his breathing. The pain was always present, often excruciating. But that didn't prevent Paey from carrying on with life. He finished law school, then did a short stint as a law clerk, but had to quit because, among other limitations, he couldn't lift the hefty law books. He never took the bar exam. Paey learned that further surgery was not an option, that to remove the screws in his back could cause paralysis. He tried to stay game, but eventually reality sunk in.

"You had a young, virile guy thinking that all you need to do is have the will and you can make it happen," Linda Paey says. "The pain, you could control that. He was convinced he could mentally muscle his way through this problem and continue to work. Ultimately, he had to face facts that he just wouldn't be able to do it. Those years were hell." Paey went on Social Security disability in 1989, his career dreams dashed. The Paeys moved to Columbus, a town in central New Jersey. There he found a doctor, a general practitioner named Stephen Nurkiewicz, who prescribed him ample doses of medication, including opiates such as Percocet and Vicodin."

As the Planet notes, however, there are many tragic cases like his:

" 'Untreated pain, it'll kill ya,' says Siobhan Reynolds, founder/director of the Pain Relief Network, based in New York. Increasingly, pain specialists and advocates characterize chronic pain as its own disease. 'If it doesn't get resolved, in time it can become its own malignancy,' says Dr. Frank Fisher of northern California. 'It can spread and metastasize to other parts of the nervous system and ultimately destroy a person's health.' Fisher recently was exonerated of running a pill mill in a rural town 150 miles from Sacramento. Authorities alleged that he indiscriminately wrote scripts for OxyContin ( uncut oxycodone ) that caused several deaths in the area. The five-year ordeal has left his practice moribund, though, and he still faces possible sanctions from the California medical board.

"Chronic pain patients not only face discrimination from law enforcement, but also from society at large. Most of us simply do not understand what protracted, severe pain is like. Many sufferers who spend periods of time untreated ( or undertreated ) will seriously consider or attempt suicide. ( Richard Paey tried twice. )

"There's also the highly ingrained notion in our society that pain somehow ennobles us. Call it the grin-and-bear-it ethic. According to several historical accounts, it wasn't all that long ago that late- stage cancer patients were denied opiate drugs so they could more closely feel the pain of Christ on the cross.

"Advocates of chronic pain patients see all this as a bunch of hooey; they maintain that with today's technology, there is no reason anyone should suffer unnecessarily.

"While most pain docs favor an integrated treatment approach, almost all prescribe opiates, and many think these drugs are the single most effective option. The American Medical Association has dubbed opiates "the gold standard" of pain treatments.

"Yet law enforcement and prosecutors -- and the public at large -- remain suspicious of them. One teen who dies of an OxyContin overdose can cause a media shit-storm that further demonizes the drugs."

Richard Paey's case is the subject of a CSDP public service ad, comparing his case with that of Rush Limbaugh. You can also download a copy of the Paey ad as a PDF (note: this file is 475K).

You can get more information about Pain Management issues by checking out Drug War Facts: Pain Management. Also check out Diversion of Pharmaceuticals.

Mandatory Madness

What happened to a man whose only crime it seems

was trying to ease his

chronic pain

BY ERIC SNIDER

"You know when you have a toothache and the pain is so severe that you

absolutely have to be seen immediately by a dentist?" says the man in the

wheelchair "Imagine if you had to grin and bear it for an undetermined

period of time. You can't see straight. You think you'll pass out, and

sometimes you do. And sometimes you pray you will."

Richard Paey, chronic pain patient, is describing how bad his body can hurt.

He suffers from what is often called "failed back syndrome," an inoperable

condition that has sentenced him to a life of pain that most of us hopefully

will never have to comprehend. This is not his only sentence. On March 5, he

was convicted of 15 counts of drug trafficking, obtaining a controlled

substance by fraud and possession of a controlled substance, which earned

him a mandatory minimum of 25 years in state prison and a $500,000 fine.

This is what Richard Paey did -- or, more accurately, this is what a jury

found Richard Paey (pronounced "Pay") guilty of: fraudulently obtaining

prescriptions of Percocet (which contains the opiate oxycodone) and Lortab

(which contains another opiate, hydrocodone), each of which exceeded 28

grams.

That's the magic number, 28 grams. Illegally possessing this amount gets you

25 years. It's the same mandatory minimum as 28 grams of heroin.

Richard Paey is the latest poster boy for advocates of chronic pain

patients, who say that this legion of silent sufferers -- from nine to 17

percent of adult Americans, according to studies -- face an ongoing culture

clash with the War on Drugs.

It's a war that pain patients are losing. The system is topsy-turvy, pain

activists say, giving medically uneducated law enforcement the power to

decide how much medicine someone is allowed to possess. Further, they

maintain that many doctors who prescribe opiates remain anxious about that

knock on the door from the law, and can thus become extremely conservative

when treating chronic pain.

The drug war has turned cops into docs and docs into cops. Physicians

constantly screen for "drug seekers" by looking for certain behaviors. They

have taken to urine-testing and interrogating folks who are desperately

trying to alleviate their pain. Pain patients often get under-prescribed or

turned away, leaving many of them in unnecessary agony. "There's so much

suffering," Paey says. "They need a war on pain."

Richard Paey knows agony. One afternoon last month, his muffled words echoed

through the dank visitors room at the Pasco County jail. He spoke to me

through thick glass. His once-athletic body, ravaged by nearly two decades

of intractable pain and five years of multiple sclerosis, sat hunched into a

crude wheelchair. Oval, wire-rim glasses framed his piercing brown eyes. His

black hair, medium-length, was unkempt, and his moustache could have used a

trim. His skin had that particular kind of pale hue that comes with extended

periods of indoor confinement.

Paey's discourse ranged from pensive musings to indignant rants. His hands

shook. While awaiting assignment to a prison, he said he spent 23 hours a

day in a bed in a small room with only jail-approved reading material. He

didn't know this during the interview, but the next day he'd be transferred

to a transitional facility in Orlando where the Florida Department of

Corrections would figure out what to do with this most unusual inmate.

Paey is not doing time for just the opiates. Each of his Percocet pills

contained 5 mg of oxycodone and 325 mg of acetaminophen (Tylenol). For

sentencing purposes though, the latter substance was weighed in as well.

Eighty-five of his pills weighed 28 grams. If Paey were sentenced for just

the oxycodone, he would've needed 5,600 Percocet tabs to earn a

quarter-century behind bars. From January to March of '97, he bought 1,200

from area pharmacies.

This inflated numbers game is just one perplexing fact in the strange and

scary case of Richard Paey, 45, husband and father of three, convict.

Consider also that Pasco sheriff's deputies surveilled him for weeks and

never found any evidence that he sold a single pill. Yet the state

attorney's office charged him with trafficking -- because it could. In

Florida, you can be charged with trafficking certain drugs, oxycodone and

hydrocodone included, without actually peddling them. You merely need to

possess them illegally.

For its part, the State Attorney's Office in Pasco offered Paey several plea

deals -- including, early on, house arrest and probation, then shorter

prison terms. For various reasons, each deal went south. Some onlookers have

characterized Paey as stubborn, saying that he put one foot in a prison cell

by not jumping at the state's plea offers. Paey came close to cutting a deal

several times, mostly at the urging of his wife, Linda, and his lawyer, but

his heart wasn't in it. Paey has maintained all along that he did nothing

criminal, that he was only medicating his own severe pain, which required

large doses, and that his scripts -- written, faxed and phoned in by a

doctor in New Jersey -- were legitimate.

After one mistrial and another guilty verdict vacated by a judge who said

Paey had not been competent to stand trial, he was convicted during a third

proceeding. The jury was not permitted to know that Paey was facing a stiff

mandatory minimum. One juror held out for acquittal but was eventually

swayed toward a guilty vote when the jury foreman convinced him that the

defendant would get only probation. The judge had no choice but to issue 25

years.

The Paeys have hired high-powered appellate attorney Eli Stutsman of Oregon,

while still retaining their regular local counsel, Robert Attridge. They

figure that, even if an appeal is successful, Richard Paey will stay locked

up for at least a year and a half. The Paey camp also holds out hope for

clemency or a pardon from governor Jeb Bush, whose own daughter has

experienced drug problems.

"I don't think the [Florida] Legislature had Richard Paey in mind when they

set up these minimum mandatory sentences," says Attridge, "The punishment in

this particular case in cruel and unusual."

On Feb. 11, 1985, Richard Paey was driving on Philadelphia's pocked and

frantic Schuylkill Expressway, on his way to class at the University of

Pennsylvania law school, when he got into a wreck that sandwiched his car

between two others. He went to the ER the next day.

Directly after the

accident, Paey began taking sizeable doses of opiate pain relievers. A few

months later, he underwent his first back surgery, but that only offered

about a year's worth of limited relief. .In 1987, he signed on for another

operation. Unbeknownst to him, he received a fusion procedure that included

an experimental "pedicle screw" implant that had been turned down for

approval by the FDA. The implants became the focus of a high-profile class

action lawsuit that was covered by the TV show 20/20. Linda Paey said her

husband never received a settlement because he got involved after a statute

of limitations passed.

His back went from bad to worse. He'd get spasms that would hamper his

breathing. The pain was always present, often excruciating. But that didn't

prevent Paey from carrying on with life. He finished law school, then did a

short stint as a law clerk, but had to quit because, among other

limitations, he couldn't lift the hefty law books. He never took the bar

exam.

Paey learned that further surgery was not an option, that to remove the

screws in his back could cause paralysis. He tried to stay game, but

eventually reality sunk in.

"You had a young, virile guy thinking that all

you need to do is have the will and you can make it happen," Linda Paey

says. "The pain, you could control that. He was convinced he could mentally

muscle his way through this problem and continue to work. Ultimately, he had

to face facts that he just wouldn't be able to do it. Those years were

hell."

Paey went on Social Security disability in 1989, his career dreams dashed.

The Paeys moved to Columbus, a town in central New Jersey. There he found a

doctor, a general practitioner named Stephen Nurkiewicz, who prescribed him

ample doses of medication, including opiates such as Percocet and Vicodin.

The two became friendly, and Paey did some small-claims legal work for

Nurkiewicz's office. In 1994, the Paeys - now with three small

children - relocated to Hudson in Pasco County because Richard's father was dying of

kidney cancer. Linda Paey, an optometrist, found work in New Port Richey.

Richard mostly stayed in bed.

The couple looked for doctors to step in for Nurkiewicz, but encountered a

lot of resistance. Staff people would tell the couple that the doctor didn't

handle chronic pain patients or that the practice didn't treat people with

failed back syndrome. Linda Paey feels that physicians avoided Richard

because of his large need for prescription pain meds and his involvement in

the experimental back surgery, a potential malpractice suit in waiting.

Dr. Nurkiewicz was sympathetic, say the Paeys, and set up a plan where he

would mail prescriptions for Percocet, Lortab and Valium. Some of the

scripts were undated; others were faxed and then verified with the pharmacy

over the phone. The system worked well for a while -- so well in fact that

in 1996 Richard Paey started taking police academy classes at Pasco-Hernando

Community College. Nurkiewicz wrote a letter to the school outlining Paey's

health status.

Since the time of his botched back surgery, Paey also had tried virtually

every conceivable treatment besides opiate drugs, including electronic

stimulation, biofeedback, spinal injections, chiropractic, massage, physical

therapy and hypnosis. None worked nearly as well as the pills.

'Untreated pain, it'll kill ya," says Siobhan Reynolds, founder/director of

the Pain Relief Network, based in New York. Increasingly, pain specialists

and advocates characterize chronic pain as its own disease.

"If it doesn't

get resolved, in time it can become its own malignancy," says Dr. Frank

Fisher of northern California. "It can spread and metastasize to other parts

of the nervous system and ultimately destroy a person's health."

Fisher

recently was exonerated of running a pill mill in a rural town 150 miles

from Sacramento. Authorities alleged that he indiscriminately wrote scripts

for OxyContin (uncut oxycodone) that caused several deaths in the area. The

five-year ordeal has left his practice moribund, though, and he still faces

possible sanctions from the California medical board.

Chronic pain patients not only face discrimination from law enforcement, but

also from society at large. Most of us simply do not understand what

protracted, severe pain is like. Many sufferers who spend periods of time

untreated (or undertreated) will seriously consider or attempt suicide.

(Richard Paey tried twice.)

There's also the highly ingrained notion in our society that pain somehow

ennobles us. Call it the grin-and-bear-it ethic. According to several

historical accounts, it wasn't all that long ago that late-stage cancer

patients were denied opiate drugs so they could more closely feel the pain

of Christ on the cross.

Advocates of chronic pain patients see all this as a bunch of hooey; they

maintain that with today's technology, there is no reason anyone should

suffer unnecessarily.

While most pain docs favor an integrated treatment approach, almost all

prescribe opiates, and many think these drugs are the single most effective

option. The American Medical Association has dubbed opiates "the gold

standard" of pain treatments.

Yet law enforcement and prosecutors -- and the public at large -- remain

suspicious of them. One teen who dies of an OxyContin overdose can cause a

media shit-storm that further demonizes the drugs.

In 1995, oxycodone and other painkillers were incorporated into Florida's

drug trafficking laws, and big-ticket sentences followed.

In a phone interview from his Tallahassee office, James McDonough, director

of the Florida Office of Drug Control, declined to comment on the Paey case,

saying he wasn't familiar enough with it. He did explain that a

proportionately high number of oxycodone deaths in recent years have

reinforced the notion that the drug should remain in a class that requires

stiff jail terms.

(Consider this: If someone is convicted of trafficking in

28 grams of cocaine, Florida statutes call for a mandatory minimum sentence

of just three years.)

Pain specialists counter that, yes, certain people are going to abuse

prescription drugs, but when used properly they are completely safe. In

fact, says Dr. Fisher, "Opioids resemble natural endorphins, which is

probably our best natural defense against pain. People have opioids in them

naturally. But when chronic pain takes hold, people simply need more of

them. [Opiate] pain treatment can be envisioned as supplementation with

natural substances, replacement therapy, like insulin for diabetes."

Here's another myth-buster: Chronic pain sufferers do not get a buzz from

opiates. "I get no euphoria," Richard Paey says. "I get no mental effects,

other than fatigue."

While the science is complicated, doctors essentially say that the effects

of the opiates are so concentrated on dulling intense pain that they simply

do not have the leftover strength to work on pleasure centers.

And further, the most sophisticated opiate medications are time-released to

be effective for up to 12 hours. Sure, addicts can crush and snort them to

disable the long-acting capabilities, but junkies aren't using them for

physical pain.

"It's ridiculous that these drugs are seen as inherently evil," says

Reynolds. "They save people's lives and families. That's more important than

the fact that people abuse them; it's just that simple."

Pasco County deputy B.J. Wright got bumped up to detective in '96 and

quickly took over the pharmacy beat. He encouraged drug store personnel to

contact him if people filled what seemed like excessive prescriptions. Soon

enough, Richard Paey popped onto his radar. Here was a guy who couldn't

possibly be taking such a volume of pills himself; he had to be selling

them, Wright figured. Deputies started watching Paey, and eight times caught

him on tape filling scripts of opiate medications -- each of which would

later weigh out in excess of 28 grams.

Wright contacted Lisa Loos of the Tampa office of the Drug Enforcement

Administration. She in turn called Dr. Nurkiewicz in New Jersey to inquire

about his large prescriptions issued to Richard Paey in Florida. The doctor

initially told her that Paey was his chronic pain patient who needed the

meds.

When Wright and Loos visited Nurkiewicz at his office on March 5, 1997,

however, the doctor started backpedaling. He asked if he was under

investigation, and the cops matter-of-factly said yes. They also casually

informed him that the penalty could run as high as 25 years in prison.

Nurkiewicz then denied writing prescriptions after 1996, thus helping build

a case against Paey for prescription fraud.

"When the DEA got involved, [Nurkiewicz] started throwing Richard Paey to

the wolves," Attridge says. "And it was amazing how the investigators bought

every word of it."

Wright still suspected Paey of drug dealing. He and other deputies tailed

him and staked out his house over the course of several weeks. Their

surveillance revealed nothing.

On March 12, 1997, Richard Paey was in the upstairs bathroom of his home.

Linda and the kids were downstairs. His mother, who had been babysitting,

prepared to leave. Around 7 p.m., a team of deputies burst into the home

with black masks and automatic weapons drawn. Flashing a search warrant, the

cops found a modest number of pills, a cache of empty pill bottles, and a

bank of computer equipment that they would claim enabled Paey to forge

scripts. They discovered letterhead from Dr. Nurkiewicz and other stuff that

also suggested forgery. They led Richard Paey from his home in handcuffs.

After being released from jail the following day, Paey entered an emergency

room with symptoms of a bleeding ulcer.

Ironically, it was during this tense time that Richard Paey received his

first truly effective treatment for chronic pain. A doctor surgically

implanted a morphine pump that establishes a steady blood level of pain

reliever. It was the first time his opiates weren't cut with large doses of

Acetaminophen. Paey continued to take periodic pills for episodes of

"breakthrough pain," but Linda Paey says he hasn't taken oral meds for a

couple of years now.

Prosecutors estimated that Richard Paey filled prescriptions for 18,000

pills over a two-year period. Shocking, huh? Paey's accusers assumed that

taking that much medicine would cause serious illness or death. Not likely,

say pain doctors. If Paey took Percocet as directed for chronic pain -- two

every four hours -- it would add up to 8,760 over two years. Add in doses of

Lortab and Valium and it's easy to understand how Paey could eat 18,000

pills in two years.

The larger issue, Paey's backers say, is that cops and prosecutors got to

decide at all.

"We're asking prosecutors instead of doctors," says Dr. Alex

DeLuca, a former pain specialist in New York, now a writer and advocate.

"Where do they get the answers? 'Sounds like too many pills to me,'" he adds

with a laugh.

Says Dr. Fisher of California:

"If you use the concept of titration, where

the doses are raised to the point that the patient functions optimally, then

law enforcement standards can decide it's too much. You have conflicting

ideologies, and law enforcement wins because they have the guns."

Such a system can cause a dangerous ripple effect. Some doctors become

fearful of scrutiny by authorities, and the potential loss of professional

standing and livelihood, as well as the possibility of incarceration. In a

scholarly paper DeLuca presented in April, "The War on Drugs, the War on

Doctors, and the Pain Crisis in America," he says prosecutions of doctors

for drug violations have risen during John Ashcroft's reign as attorney

general.

There's even a name for doctor's anxieties over being labeled a drug dealer:

"The Chilling Effect." DeLuca defines it as "the withdrawal by physicians

from the appropriate treatment of pain resulting from fear of litigation."

Dr. Clifford A. Bernstein, a pain specialist in Beverly Hills, Calif., much

prefers other treatments to opiates, but he still prescribes them. He says

the way to avoid the Chilling Effect is to "keep good records. There's

nothing wrong with people being on narcotics, but you have to assess the

patient, warn about the dangers of these drugs and justify their use in your

notes."

Apprehensive pain doctors blame the War on Drugs for the current

predicament. It's a war that targets not just dealers and dopers, but

doctors and their patients too. DeLuca writes:

"The root cause of the

widespread undertreatment of pain can be traced directly to the systematic,

nationally coordinated, relentless harassment, arrest and prosecution of

thousands of American physicians, many of whom had been engaged in nothing

other than the standard care of pain and addiction of the day."

The big losers in all of this? Chronic pain sufferers.

Take the case of Robert Stevens, one of Dr. Fisher's patients, who has a

ruined back. Five years ago, before Fisher was busted, Stevens, who was on

Social Security disability for a mental condition, rode a bike several miles

a day and enjoyed a decent quality of life. He took a maintenance dose of

OxyContin.

With Fisher gone, Stevens immediately reduced his dose to the lowest he

could stand. "I figured I needed to wean myself off," he explains. "But I

wasn't prepared for the amount of pain I would be in. It was four years

since I'd been in that kind of pain."

Stevens soon became bed-bound. "It felt like an abscess tooth for months

upon months with no escape," he says by phone, the pain audible in his

voice. "I got headaches from gritting my teeth all the time, my legs cramped

up. I thought, 'This isn't living; why don't I just stop it?' Fortunately, I

had a support system of people telling me to hang on, or I wouldn't be here

now."

Stevens finally found a doctor willing to treat him in Fresno. Once a month,

he would make the 656-mile round trip to fill his OxyContin script. It was

worth it. But then his doctor dropped him, saying he had concerns about the

toll the car rides were taking.

Stevens takes methadone now, which he says is about half as effective as

OxyContin. He's in bed most of the time. "I've got paperwork to start going

to mental health [care] for suicidal thoughts," he says in a monotone. "And

depression."

Studies suggest there are a lot of Robert Stevenses in the country. Their

supporters offer a simple solution: Let physicians assess pain patients and

prescribe them the medication they need. And keep law enforcement out of the

doctor's office.

"We need to have the remedicalization of the whole arena,"

says Reynolds of Pain Relief Network. "Move controlled substances from the

Justice Department over to the FDA; don't classify them according to

superstitious notions; make distinctions between substances based on medical

judgments."

Before the first trial in late 2001, Linda begged Richard to accept a period

of house arrest, followed by probation. He already was under a sort of house

arrest, she argued. Richard finally agreed, but when he got in front of the

judge to seal his plea bargain, he balked, then broke down sobbing. The

judge canceled the deal.Two arduous trials ensued, each thrown out or

overturned. And still the State Attorney's Office in Pasco pursued the drug

trafficking charges. The prosecution made more offers, but each required

jail time, and Paey passed.

"They should've dropped the trafficking charges," Linda Paey says, her voice

rising. "They held this huge hammer over our heads, and then said they were

being nice guys by offering plea deals. They should not have charged him

with the trafficking statute knowing he was not a trafficker."

But the Paeys overestimated the court's inclination toward mercy. Richard

was, in effect, punished in part for not playing by the rules. The Paey camp

insisted that the charges be dropped or reduced without concessions from

them -- concessions that would essentially admit to a criminal act -- and

such obstinacy does not play well to the prosecutorial mindset.

Assistant State Attorney Scott Andringa, the lead prosecutor, explained it

this way: "As a trial lawyer, normally you charge the highest crime that you

can prove. If it goes to trial, you might as well lean on that. Then there's

[the option] to plead the case out. I understand someone wanting to have

their day in court � But they have to accept that with that there's a risk,

and in the case of Richard Paey it was a 25-year mandatory minimum, which he

knowingly and willingly accepted."

"While I have sympathy for him, the system did what it does. Everyone did

their job. We made a decision based on laws passed by the Legislature and

signed by the governor. We made the right filing decision as evidenced by

the jury's verdict. I don't see this as an issue of whether our office did

the right thing - I have no personal or professional regret about what we've

done in this case."

When asked if 25 years in state prison was a proper punishment for Richard

Paey's crime, Andringa said, "It's not appropriate for me to give my

personal opinion [about that]."

Reynolds replied passionately to Andringa's points in an e-mail:

"When you

take power away from judges, you give it to prosecutors. If they have the

power to induce pleas with the threat of draconian sentences, the defense

attorneys are reduced to making deals that minimize the damage done to the

lives of defendants who, by the way, have at the time of making the deals,

been convicted of absolutely nothing. What goes on, therefore, is a

systematic denial of due process, a parallel criminal justice system that

consists only of targeting and punishment, a parallel system that is

essentially operating outside judicial review."

Eli Stutsman, the Paeys' newly acquired appellate attorney, declined to

comment on strategies, saying that he hadn't even received the trial

transcript yet. But Attridge, who defended Paey at his last trial, said

their main thrust for appeal would be "the perjured testimony of the doctor,

which was what the verdict was based on. The state should've known it was

perjured. He's entitled to a new trial."

Although Richard Paey was not allowed phone calls or visitors during his

stay in the transitional facility, he did get a letter to Linda. They'd

shorn his hair and put him in the infirmary because of his morphine pump.

He received some disquieting news. Department of Corrections policy is not

to refill morphine pumps, although no decision had yet been made on his

particular case. Stutsman called the DOC and impressed upon officials the

importance of continuing the treatment.

In early June, Paey was moved to his permanent facility, Zephyrhills

Correctional Institution in Pasco County. He wrote his wife and said,

"I was

told they're going to refill my pump." Then, in a letter Linda received on

June 7, he wrote, "I haven't heard anything about my [morphine] pump, other

than the staff doctors remark that he didn't know how to handle one of them.

It's been said, though, that I was sent here primarily because Zephyrhills

could take care of the pump."

Meanwhile, Linda Paey, who for so long had fought the good fight, must

confront reality. "Now they're processing him to be in prison for 25 years,"

she says, her voice cracking. "It's more than depressing. It's scary. This

wasn't supposed to happen."

Information for portions of this story was culled from court testimony and

depositions. Contact senior writer Eric Snider at 813-739-4853 or at

[email protected].

Richard Paey

Richard V. Paey was sentenced on April 16, 2004 to a mandatory minimum sentance of 25 years and fined $500,000.

Paey, in his wheelchair with a morphine pump sewn into his ruined back, will live out-what for him is a death sentence-in a Florida prison for possessing the medicine that he requires to survive.

Judge David D. Diskey heard Linda Paey�s pleas for mercy, but could not exercise judicial discretion because of a mandatory minimum sentancing. �This is the problem for the Florida state legislature and the governor,� Judge Diskey said.

�Richard Paey was prosecuted three times in the very same district that is represented by Senator Mike Fasano, the sponsor of Florida�s Prescription Monitoring Bill (Senate Bill 580). Sen. Fasano�s claim that prosecutors won�t use private medical information gathered in government computers against patients in pain, is exposed for the hollow assurance it is,� Executive Director of PRN, Siobhan Reynolds said.

Senate Bill 580, and it�s companion bill�House Bill 397, would allow more government intrusion into medical privacy, further chilling legitimate pain management and allowing prosecutors to attack yet more people in pain like Richard Paey.

Pain Relief Network is working with the Paey family to develop an appeal and to keep the hope alive. PRN commends Richard and his family for their show of extraordinary character and perseverance. The pain community owes them an enormous debt of gratitude.

I just got back from Florida where I witnessed Richard Paey get sentenced. I am dismayed to read that he is being characterized as stubborn. It is shocking that the media and prosecutors have forgotten that guilt and innocence are supposed to be at issue in our criminal courts, not whether defendants are sufficiently compliant with authority, as authority would like for them to be.

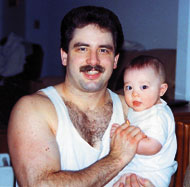

Richard Paey is a remarkable, courageous, principled man and his wife Linda is a paragon of wifely allegiance and dedication. The two of them have raised three beautiful, well- adjusted children, two teenaged daughters and an 11-year-old boy.

Richard says that the DEA and the Pasco County Sheriff essentially put it to him and his doctor, "Who's going down?" The doctor has answered by testifying against Richard in an increasingly dishonest fashion in the three prosecutions, while Richard has been unwilling to turn on him.

Richard's life has been destroyed by undertreated pain, society's obsessive/compulsive and immoral focus on addiction, and abuse at the hands of the powerful and calloused. He took his principled and courageous position because he wants to make the world aware of what actually happens to patients who require high doses of opioid medications to survive.

He did not commit prescription drug fraud; the doctor specifically authorized each of the prescriptions over the phone. The doctor's current denial of ever having written or authorized any of the prescriptions in question is controverted by all the available evidence.

Like much of what I've observed in the witchhunt trials of the doctors, the jury appears to have been convinced not by the weight of the evidence but by opiophobia and the prejudicial atmosphere that pervades courtrooms whenever pain care is at issue.

The government, on the other hand, has set out to convict a sick person for drug trafficking and appears to be punishing Richard for maintaining his innocence.

I hope never to hear the word "stubborn" used to describe Richard Paey again.

He is a principled and courageous man who has sacrificed himself to demonstrate the hidden and denied reality facing patients in pain.

We all owe him and his family, our unflagging support.

Please support our efforts to help Richard and his family by donating whatever you can to Pain Relief Network. We have established a special fund for Richard's appellate expenses and to fund our media/political work in support of his case.

Click here to contribute

All contributions are tax-deductible.

We realize that many of our members are patients in pain and so are limited in their ability to lend financial assistance. This is why we do not charge any dues or fees for membership in PRN.

But for those of you who are able to contribute, we ask you to dig down deep. We can assure you that your money will be spent in the most efficient and targeted manner possible.

Thank you for your help.

Siobhan Reynolds

Founding Executive Director

Painreliefnetwork.org

Florida Pain Patient Faces Decades in Prison for Pain Medication

4/9/04 Richard Paey, 45, of Hudson, Florida is disabled. Injured in a traffic accident in 1985 while attending law school at the University of Pennsylvania, Paey suffered a severely herniated disk in his lower back. A first surgery failed, and a second operation, an experimental procedure involving screw inserted into his spine, only aggravated matters. It left his backbone splintered and the mass of nerves surrounding it mangled. Paey, who relies on a wheelchair for mobility, was left in excruciating chronic pain, which he treated with prescribed opioid pain relievers.

But Paey's odyssey from being just another of America's tens of millions of chronic pain sufferers to a Florida jail cell was about to get underway. Paey and his family had been living in New Jersey, where a physician prescribed large amounts of opioid pain relievers for Paey, but when they moved to Florida, they could not find doctors willing to provide the high-dosage prescriptions needed to fend off the pain that tormented him.

Paey, who has also been diagnosed with advanced multiple sclerosis, resorted to filling out prescription forms obtained from his New Jersey doctor and eventually came to the attention of the Drug Enforcement Administration and the Pasco County Sheriff's Office. Investigators reported watching Paey and his wheelchair roll into one pharmacy after another to pick up fraudulent prescriptions, adding up to more than 200 prescriptions and 18,000 pain pills in a year's time.

No one could take so many pills, investigators suspected. Paey must be a drug dealer. And they charged him as one, even though no one has ever presented any evidence that Paey did anything with the pain pills except ease his own pain. Now, after two mistrials, plea bargain offers made and withdrawn, and plea bargain offers rejected by Paey, prosecutors have managed to win a conviction. A week from today, a Florida judge will decide Paey's fate, although if the judge follows state law, there is not much to decide. As a convicted Florida "drug trafficker", Paey faces a mandatory minimum sentence of 25 years in prison.

In a last minute bid to win freedom for Paey, who is currently imprisoned in the hospital wing of the Pasco County Jail and is being treated with a morphine pump while in jail, his attorneys will use the occasion of next Friday's hearing to ask that the verdict be dismissed on the grounds that Paey's New Jersey physician, Dr. Steven Nurkiewicz, lied on the stand when he testified that he did not give Paey permission to fill out undated prescription forms.

"The state knew Dr. Nurkiewicz was lying when he said he did not provide the prescription forms and that he only prescribed small numbers of pain pills, but they said he wasn't on trial, and they won't charge him with perjury," said Paey's wife Linda. "We tried to get a mistrial, but they were still able to put Nurkiewicz on the stand knowing that he had lied," she told DRCNet. "They feel like the end justifies the means, that my husband is a bad person, and that they've invested too much money in prosecuting him to let him get away. Now they will lose face if they drop the charges," she said.

"We were so na�ve when this began," she said. "They accused him of selling the medicine and we said no, he's a pain patient. I thought that once they saw that was true, they would understand. But no. They not only charged him as a drug trafficker, but they harassed his doctors to stop him from getting more pain medication."

Paey's family and a growing number of supporters are not merely relying on the courts for justice, but taking his case to the court of public opinion. A letter writing campaign to local newspapers is underway, and the St. Petersburg Times has editorialized on Paey's behalf. Paey has also drawn support from national organizations including the Pain Relief Network (http://www.painreliefnetwork.org) and the November Coalition (http://www.november.org), a group working to end the drug war and free its prisoners. This evening, supporters will hold a vigil outside the Pasco County Courthouse in Port Richey.

"Richard Paey is a hero, not a criminal," said Siobhan Reynolds, founder and executive director of the Pain Relief Network, as she prepared to board a flight for Tampa Wednesday.

"The more people hear about this case, the more disturbed they are. He refused plea bargains because he would not be complicit in criminalizing his own efforts to save his own life," she told DRCNet. "This is about medicine and medical care, not about illegal drugs or drug trafficking, and it is startlingly clear that local prosecutors and the DEA have totally lost track of that distinction."

The Pain Relief Network and other Paey supporters will ask the prosecutors to not stand in the way of the acquittal motion, Reynolds said.

"We are calling on them to join the motion to acquit. This was not a real crime, only a statutory one," she said. "We want them to do the right thing for this suffering individual."

The conviction of Richard Paey comes as Florida is in the midst of its own version of drug czar John Walters' war on prescription drug abuse. Alongside such high profile actions as the investigation of Rush Limbaugh and the nearly monthly arrests of pain management physicians, the Florida legislature has been at work crafting a prescription monitoring bill that would allow doctors and law enforcement to access a database showing prescriptions to all potentially addictive drugs statewide.

As part of the White House's National Drug Control Strategy, Walters is pushing for more states to join the 15 that already have such programs. They would help reduce abuse by allowing physicians and law enforcement to spot patients seeking multiple prescriptions, Walters said. Paey's representative, state Sen. Mike Fasano, is sponsoring the bill in the state Senate. The bill would protect patient privacy by making it a felony to unlawfully divulge patient information, Fasano told the Orlando Sentinel in February.

But Paey's case shows the danger of such a database, said Reynolds.

"Richard Paey was prosecuted three times in the very same district that is represented by Senator Mike Fasano, the sponsor of Florida's prescription monitoring bill. Fasano's claim that prosecutors won't use private medical information gathered in government computers against patients in pain, is exposed for the hollow assurance it is," Reynolds said. "Law enforcement already looms over medicine to such an extent that patients with the highest dose requirements, those with the most severe pain, can't find medical help. Prescription Drug Monitoring Programs only ensure that the under-treatment of pain will continue to plague our most vulnerable citizens and their families."

Still, the Senate bill and its companion bill in the Florida House are moving.

Meanwhile, Paey's supporters are gathering for a last minute effort to bring him home.

"John Chase of the November Coalition and Siobhan Reynolds have really been working hard to get the word out," said Linda Paey. "I couldn't do all this myself. But we are encouraged by all the support we are finding out there. The Times editorial certainly helped. And my coworkers and neighbors have been very supportive. There are people I don't know who pull up in my driveway and offer their support," she said. "It's a little shocking." She has also had nibbles from the CBS news program 60 Minutes, Paey said.

Linda Paey is not pleased with local law enforcement and prosecutors.

"They have done nothing but try to prosecute my husband, and they used the most disgusting tactics. They're used to threatening everyone with long mandatory minimum sentences, then getting them to cop a plea and get probation," she said. "If these people are so dangerous they need mandatory minimum sentences, why do they turn around and give them probation?" she asked.

"This case should not even be in the courts," Paey added. "Cases like this should be given to the medical board to see if there was any wrongdoing to begin with. Instead, they assume the doctor is over-prescribing or the patient is abusing the drugs, but they don't know that. It's an easy way for cops and prosecutors to look tough on drugs."

"My husband refused to plea bargain because he believes this prosecution is wrong, that this should not be happening. I haven't been able to convince him otherwise. Now he is collateral damage in the war on drugs."

And now Richard Paey and his supporters have only a week in which to act to prevent him from being sent to prison for 25 years. Paey's case is not only an object lesson in the way a dogmatic war on drugs creates new victims, but also a sad commentary on the state of our nation's judicial systems. When someone is punished for actually trying to defend himself against criminal charges, as opposed to accepting a plea bargain of guilt, something is very much amiss in the halls of justice.