From MedScape

Pharmacologic Management of Breakthrough or Incident Pain

Introduction

Chronic pain can be defined as unrelenting, intractable pain commonly caused by injury or disease, and often occurs after healing is complete; chronic pain can also exist in the absence of disease. According to pain researchers John Loeser and Ronald Melzack, chronic pain is distinguished from acute pain in that therapies for the former only provide transient relief and do not resolve the underlying pathologic and healing processes: "Chronic pain will continue when treatment stops."[1] The American Pain Society has adopted the definition of chronic pain offered in the Textbook of Pain (4th edition, 1999):[2]

"Generally considered to be pain that lasts more than 6 months, is ongoing, is due to non-life-threatening causes, has not responded to current available treatment methods, and may continue for the remainder of the person's life."

The intensity and persistence of chronic pain may be influenced by physical, emotional, and social and other environmental stresses. Of note, the intensity of chronic pain may not be related to the extent of tissue injury or other quantifiable pathology, and the persistence of pain may be due to factors other than the initial tissue damage or insult that triggered the onset of pain.[1]

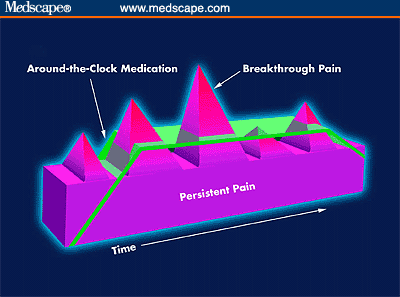

Chronic pain of moderate to severe intensity is typically associated with advanced stages of cancer and may be due to tumor invasiveness or metastasis, or to current or prior chemotherapy or radiotherapy.[3] Moderate to severe chronic pain is also encountered outside of the cancer setting, and may be associated with noncancer disorders such as arthritis, sickle cell anemia, low back pain, headaches, neuralgia, and fibromyalgia.[1,4,5] Frequently, patients with chronic cancer or noncancer pain experience relatively short episodes of worsening pain, which are referred to as breakthrough or episodic pain.[6,7] Thus, chronic pain can be thought of as consisting of two components: a relatively constant component (baseline pain) and an intermittent component superimposed on the baseline pain (breakthrough pain).

Regardless of its cause, chronic pain negatively impacts quality of life, often profoundly affecting mobility, mood, personality, and social relationships. Patients typically experience concomitant decreased overall physical and mental functioning, depression, sleep disturbance, and fatigue.[4,8,9] Because of the multidimensional impact of chronic pain (ie, severely reduced physical, psychological, and social well-being), pain is only one of many issues that must be addressed in the management of patients with chronic pain. Optimal pain management of patients with chronic pain frequently requires both pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic interventions. Nevertheless, pharmacologic therapy remains the foundation of cancer pain management. Effective pain management is best achieved by a team approach involving patients, their families, and healthcare providers.[10] It is important to note that this activity is not a comprehensive review of all chronic pain management strategies; rather, this article considers only the pharmacologic management of moderate to severe chronic pain, including breakthrough pain, in cancer and other patient populations.

The use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of chronic pain represents a key component of a comprehensive care program. Indeed, long-acting opioids have been shown to improve the quality of life in patients with chronic pain of both cancer and noncancer etiology.[11] Opioid analgesics are considered the cornerstone of cancer pain management, especially for the relief of moderate to severe chronic pain.[12,13] Opioids act by blocking the repeated transmission of pain signals and the resulting neural remodeling underlying the pathophysiology of chronic pain (discussed in detail below). Although the appropriate use of opioids can lead to effective control of chronic pain, including breakthrough pain, these drugs do not wholly eliminate the pain. The goal of therapy is the control of pain and rehabilitation so that the patient can regain some degree of their former functional status. Opioids are administered with the aim of easing or reducing pain and suffering while improving physical and mental functioning.[4]

For a variety of reasons, chronic pain is often undertreated, particularly in the noncancer patient population. Opioids are the strongest pain relievers available, but because of their potential for abuse, they are classified as scheduled drugs by the US Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA), under the Controlled Substances Act of 1970. The continued stigmatization of opioids and their prescription, coupled with often unfounded and self-imposed physician fear of dealing with the highly regulated distribution system for opioid analgesics, remains a barrier to effective pain management and must be addressed. Clinicians intimately involved with the treatment of patients with chronic pain recognize that the majority of suffering patients lack interest in substance abuse. In fact, patient fears of developing substance abuse behaviors such as addiction often lead to undertreatment of pain. The concern about patients with chronic pain becoming addicted to opioids during long-term opioid therapy may stem from confusion between physical dependence (tolerance) and psychological dependence (addiction) that manifests as drug abuse. This misunderstanding can lead to ineffective prescribing, administering, or dispensing of opioids for chronic pain, resulting in undertreatment.

Nevertheless, the barriers to effective pain management are slowly breaking down, especially in the noncancer patient setting. Jointly, the DEA and 21 health organizations, including the American Medical Association, have written a consensus statement that supports the use of opioid analgesics for the treatment of pain while recognizing their potential for abuse.[14] In addition, many professional organizations, including the World Health Organization (WHO), the American Pain Society, and the American Medical Directors Association, have independently issued consensus statements supporting the use of opioids in select patients with chronic noncancer pain based on accumulated evidence indicating that patients treated with opioids for chronic noncancer pain show improvement in analgesia and/or level of function.

Thus, although state and local laws restrict the medical use of opioids to relieve pain, awareness of and adherence to these guidelines enables the physician to use these effective agents in the management of chronic pain. Indeed, the Joint Committee on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO), which accredits nearly 80% of the hospitals in the United States, has developed standards for assessment and management of pain for patients and has begun monitoring compliance with these standards.[15]

Evaluation, Assessment, and Diagnosis of Chronic Pain

A comprehensive assessment of the patient with chronic pain -- regardless of its etiology -- is essential to developing a pain management plan. The purpose of the initial assessment is to identify the causes, contributing factors, and pathophysiology of the pain (ie, visceral, somatic, neuropathic) and to determine the intensity of the pain and its impact on the patient's ability to function. The assessment must describe the pain symptoms and the relation between the pain and the disease; it should also help or attempt to clarify the impact of the pain and other existing conditions on the quality of life. An initial assessment must include a detailed history, physical examination (including a neurologic exam), psychosocial assessment, and diagnostic evaluation.

Because pain is a subjective experience, a patient's self-report should be the foundation of an initial assessment. The self-report should contain information on temporal features of the pain (onset, pattern, and course), its location (primary sites and patterns of radiation), its severity (using a descriptive or numeric scale), quality, and factors that exacerbate or relieve the pain. In cases where the cause of pain is not apparent, factors that could have triggered the onset or worsening of pain, such as physical therapy or radiotherapy, should be considered and explored with the patient. The self-report, combined with information from the physical examination and review of laboratory and imaging studies, usually defines a discrete pain syndrome, identifies disease and the relation between the pain and specific lesions, and allows inferences about pain pathophysiology. Any decision regarding additional assessments or specific therapies should be guided by this information.[8,10]

The selection of appropriate analgesic therapy is based upon the intensity of the patient's pain. After starting treatment, the patient's response to the analgesic regimen and to its side effects should be monitored at regular intervals. Any change in pattern of pain or the development of new pain should be evaluated, and the treatment plan should be modified as needed.

Pharmacologic Management of Chronic Pain: Overview

There are several paradigms for the pharmacologic management of chronic pain. Perhaps the most familiar is the "analgesic ladder," which was originally developed by the WHO for the selection of an appropriate analgesic therapy for cancer pain,[16] and which has subsequently been adapted for chronic noncancer pain[17] (Figure 1). According to the WHO 3-step analgesic ladder model, the choice of analgesic therapy is based upon the intensity of the patient's pain: mild to moderate pain should be treated with nonopioids such as acetaminophen or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs); for moderate to severe pain, a combination of a nonopioid and a weak opioid should be used; for severe pain, a strong opioid is recommended.[12,13,16]

Figure 1. "Analgesic ladder" for chronic (left) and noncancer (right) pain. Adapted from World Health Organization. World Health Organ Tech Rep Ser. 1990;804:1-73; and Roth SH, Reder R. Resid Staff Physician. 1998;44:31-36.

The specific goals of pharmacotherapy for severe chronic cancer pain are the control of persistent pain with fixed-schedule (around-the-clock [ATC] or continuous) opioid analgesics and the relief of breakthrough pain with rescue dosing as needed.[3,18,19]

In chronic noncancer pain, opioids are reserved for use in those patients for whom nonopioid medications and nonpharmacologic methods produce inadequate relief of pain and negatively impact the patient's quality of life.[20] However, as shown in Figure 1, the stepped method for managing pain of varying intensity in patients with arthritis, adapted from the WHO ladder, does not relegate opioids to the therapy of last resort.[5] Portenoy[21] has proposed guidelines for the use of opioids in noncancer chronic pain, which focus on achieving optimal efficacy and safety but also include consideration of the potential risks of substance abuse with long-term opioid therapy. The guidelines thus help to anticipate and recognize drug abuse problems and assist in meeting regulatory requirements.

According to the "Portenoy guidelines," opioid use should be considered after treatment with all other analgesics has been unsuccessful, and may be contraindicated when there is a history of substance abuse or severe character pathology. In addition, it is recommended that a single practitioner be responsible for treatment, that goals of treatment be established prior to initiation of therapy, and that the risks of treatment (ie, addiction, cognitive impairment, and physical dependence) be made known to the patient. Any evidence of abuse (eg, drug hoarding, uncontrolled dose escalation) may require discontinuation of drug and warrant intervention by an addiction specialist. Proper and complete documentation is mandatory, as is a comprehensive reassessment for each visit.

Opioids for the Management of Chronic Pain

A key benefit of using opioids to manage chronic pain is that they can be administered by a variety of routes. Compared with other analgesics, opioids are highly effective, easily titrated, and have a favorable benefit-to-risk ratio. According to cancer pain specialist Declan Walsh, "The single biggest problem in opioid drug therapy is underdosing."[3]

The beneficial analgesic effect of opioids, their potential side effects, and the risks associated with their use can vary considerably among individuals.[22] Some patients may not experience adequate pain control despite appropriate dose adjustments, whereas others may develop intolerable adverse effects to a particular opioid. These differences may be related to variance in genetic expression of opioid receptors, as well as to differences in the metabolism of these agents.[23]

Opioid therapy must be individualized, such that each dose would provide a balance between effective analgesia and acceptable side effects. To achieve this goal, a gradual adjustment of the dose is usually required. Moreover, the appropriate agent that meets this goal may only be found through sequential trials of different opioids.[24] As with the use of all medications, potential side effects should be discussed with the patient.

In terms of the sensitivity of pain types to opioids, visceral pain responds best, followed by somatic pain, and neuropathic pain. Neuropathic pain is relatively insensitive to opioids, and often necessitates the use of adjuvant analgesics, such as antiepileptics and older antidepressants, to obtain optimum pain control.[3]

Normal pain sensation results from the activity of two neural systems working in tandem. Briefly, afferent peripheral nociceptors (nonmyelinated C fibers and myelinated A delta fibers), which carry pain signals, synapse with highly organized neurons in the dorsal horn of the spinal cord. The signals are then transmitted to the deep structures of the brain, specifically to the thalamus via the spinothalamic tract and to other, less well-described pathways. From there, the signals are passed to various areas of the cerebral cortex where they are processed. As these signals pass through the brainstem, they activate the antinociceptive system, an endogenous descending analgesic pathway, causing the release of endorphins from the periaqueductal gray matter as well as enkephalins from the nucleus raphe magnus. These endogenous opioids bind to and activate receptors on presynaptic and postsynaptic cells (mu receptors) and inhibitory interneurons (delta receptors), which, in turn, leads to a series of cellular events that prevent the transmission of pain signals.[25]

Continual or repeated transmission of pain signals leads to the remodeling of pain pathways, making them hypersensitive to pain signals and resistant to antinociceptive input, and underlies the pathogenesis of chronic pain. These neural changes, known as neural plasticity, result in persistent pain often after healing is complete (or in the absence of disease), as well as the spread of pain to areas other than those involved with the initial injury or disease.[1,4] Opioid analgesics mimic the effects of endorphins and enkephalins by blocking the repeated transmission of pain signals and the resulting remodeling by activation of the antinociceptive system.

Types of Opioids

Opioids are classified as pure agonists, partial agonists, or mixed agonist-antagonists, depending upon the specific receptors to which they bind and their specific activity at these receptors. Pure agonists are so named because they mimic the action of endogenous opioids most closely, and their effectiveness increases with increasing dose. Consequently, pure agonists such as morphine are the most commonly used opioids in the management of severe chronic cancer pain. Of note, these agents do not reverse or antagonize the effects of other pure agonists given simultaneously.

Partial agonists have less effect than do pure agonists at opioid receptors. Agents in this group include pentazocine, butorphanol, dezocine, and nalbuphine. Mixed agonist-antagonists, such as buprenorphine, block one type of opioid receptor while activating a different opioid receptor.[10,13] The analgesic effectiveness of both partial agonists and mixed agonist-antagonists is limited by a dose-related ceiling effect. Consequently, these groups play a minor role in the management of cancer pain.

Long-acting opioids are typically recommended for the treatment of severe chronic cancer pain, and for select patients with chronic noncancer pain. Short-acting, or immediate-release, opioids are generally recommended when opioid therapy is being initiated for the first time or as rescue therapy for episodes of breakthrough pain. Once stable, patients can usually be switched to a controlled-release or slow-release formulation. Clinical experience suggests that selection of an effective pain regimen for the patient with chronic pain, combined with aggressive management of side effects, leads to improved overall functioning and quality of life (Table).

Table. Opioid Agonists Commonly Used in the Management of Chronic Pain

| Agent | Formulations | Comments |

| Morphine | Several short- and long-acting formulations: injectable (IV, IM, SQ); immediate- and controlled-release (8-24 hours duration of action) tablets and suppositories; immediate-release syrup; controlled-release suspension | Standard of comparison for opioids |

| Hydromorphone | Several short- and long-acting formulations: injectable (IV, SQ); immediate- and controlled-release (with 8-12 hours duration of action) tablets or capsules; rectal; intraspinal | High bioavailability (78%) with SQ infusion |

| Oxymorphone | Short-acting formulation formulations: injectable (IV, IM, SQ) and rectal formulations |

|

| Codeine | Short- and long-acting formulations: immediate-release tablets (coformulated with NSAIDs); controlled-release single-agent tablets | Commonly used for mild to moderate pain |

| Dihydrocodeine | Short- and long-acting formulations: immediate-release tablets (coformulated with NSAIDs); controlled-release single-agent tablets |

|

| Oxycodone | Short- and long-acting formulations: immediate release tablets (coformulated with NSAIDs); controlled-release single-agent tablets and syrup | High bioavailability (60%) with oral formulation; single agent effective for severe pain |

| Hydrocodone | Short- and long-acting formulations: tablet, syrup, and sustained-release capsules (8-12 hours duration of action); coformulated with acetaminophen |

|

| Methadone | Oral and parenteral formulations | Used as a second- or third-line opioid for cancer pain; has a number of unique characteristics: excellent oral and rectal absorption, no known active metabolites, long plasma half-life (24 hours) |

| Levorphanol | Oral and parenteral formulations | Used as a second-line agent for chronic pain |

| Fentanyl | Short-acting, rapid-onset oral transmucosal formulation, optimal dose found by titration and not predicted by ATC dosing; long-acting transdermal patch provides 72 hours of stable drug delivery, 12-hour delay in onset and offset of action | Transdermal formulation: potency relative to other opioids not established |

| Tramadol | Long-acting formulation: controlled-release tablets | For mild to moderate pain; not a scheduled analgesic; weak opioid agonist; also inhibits reuptake of norepinephrine and serotonin |

IV, intravenous; IM, intramuscular; SQ, subcutaneous; NSAIDs, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs; ATC, around-the-clock.

Adapted from: National Cancer Institute. Pain PDQ, Health Professional Version. Available at: http://www.nci.nih.gov/cancerinfo/pdq/supportivecare/ pain/healthprofessional/.

Accessed February 13, 2003. Cherny NI. The management of cancer pain. CA Cancer J Clin. 2000;50:70-116.

Routes of Opioid Administration

Opioids may be administered by several routes: oral, transmucosal, rectal, intravenous, subcutaneous, transdermal, and intraspinal (intrathecal and epidural). Individualized therapy should take into consideration several factors, including prior response to opioids and patient preference to route of administration. Initiating therapy with a short-acting oral agent is preferable, especially in the opioid-naive patient. Transitioning to a continuous-release agent, whether oral or transdermal, may easily be accomplished once tolerance to opioids is demonstrated.

Assessing the patient's response to several different oral opioids is recommended before switching to another route of administration. When changing drugs and not route of administration, comparisons must be made at equianalgesic doses. When changing route of administration and not drug, the dose of the drug must be adjusted; this is particularly important when switching between oral and parenteral routes if the opioid undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism.

Rectal administration is a safe, inexpensive, and effective route for delivery of opioids (and nonopioids) when a patient has nausea or vomiting or is otherwise unable to take medication by mouth or prefers another route. Transdermal (fentanyl) patches provide long-lasting analgesia (up to 72 hours) and typically are used for relatively stable analgesic requirements. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC) is used for the relief of breakthrough pain primarily because of its rapid absorption and consequent rapid therapeutic effect (within 15 minutes).

Parenteral methods should be used only when simpler, less demanding, and less costly methods are inappropriate, ineffective, or unacceptable to the patient. This route may be useful if a patient cannot swallow and intravenous access is established. Intravenous administration provides a rapid onset of analgesia (within 2 to 10 minutes), but the duration of action may be shorter than with other routes. The subcutaneous route is as effective as the intravenous route, and may be more convenient in some situations, such as in home or hospice care. Because the bioavailability of opioids administered by a parenteral route (eg, morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, and codeine) is generally 2-3 times that of the oral route, when switching from the oral to the subcutaneous and intravenous routes, the dose must be decreased by one half or one third. Opioids administered parenterally may be given either intermittently (usually every 4 hours) or by continuous infusion.

In general, other routes of opioid administration are not recommended because they are either painful (ie, intramuscular) or are only useful in specific circumstances. For example, patient-controlled analgesia is used to determine an opioid dose when initiating therapy, and intraspinal administration of opioids (epidural or intrathecal) can be helpful in a very small select group of patients with intractable pain, such as those with bilateral or midline pain in the lower part of the body, or when systemic agents provoke intolerable side effects or inadequate pain relief.[10]

Because chronic pain of both cancer and noncancer etiology share the same neural mechanisms, treatment approaches may be extrapolated from the management of chronic cancer pain to pain of other causes. Based on the findings of several studies and reports demonstrating analgesic efficacy and acceptable side effects with opioid therapy in a wide range of chronic painful conditions (eg, osteoarthritis, sickle cell anemia, back pain, phantom limb pain, neuropathic pain, and headache), many professional organizations as well as expert groups in pain management, including the American Pain Society, now support the judicious use of opioids for selected patients with chronic noncancer pain.

Side Effects of Opioids

The more common side effects of opioids include constipation, nausea, sedation, and cognitive impairment (ie, confusion and delirium). When the cause of specific side effects is thought to be due to the accumulation of active metabolites, a switch to another opioid may mitigate the side effects.[10,13]

All patients on ATC opioid therapy need to be given laxatives prophylactically. Opioid-induced constipation is a frequent cause of chronic nausea and appears to be dose-related; it is characterized by large variability in individuals and is mediated by both central and peripheral mechanisms. Complete tolerance to this effect generally does not develop, and most patients require laxative/stool softener therapy for as long as they take opioids.[10,13]

By contrast, although nausea and vomiting is a common side effect of exposure to opioids, tolerance tends to develop, such that the effect usually disappears within the first weeks of treatment. Prophylactic use of an antiemetic is not necessary routinely, but an appropriate antiemetic is usually effective in limiting nausea and vomiting and should be used during the initiation phase of opioid therapy. In some patients, nausea and vomiting may persist beyond the opioid-initiation phase or occur de novo in patients on long-term opioid treatment and may become chronic in nature.[10,13]

Opioid-related central nervous system side effects include sedation, confusion and delirium, and myoclonus. Sedation and cognitive impairment commonly occur with the initiation of therapy or with dose escalation, but tolerance tends to develop to these effects, such that they usually disappear within the first week of treatment. In some patients, sedation and cognitive impairment may persist. Certain individuals may manifest a paradoxic stimulation with certain opioids, which may become attenuated with opioid rotation. Myoclonus, although common, is mild and infrequent; tolerance develops to this effect as well.[10,13]

Breakthrough Pain in Cancer Patients

In 1990, Portenoy and Hagen[6] proposed a standard definition of breakthrough pain in their prospective study of breakthrough pain in cancer patients. Breakthrough pain was defined as a transient increase in the intensity of moderate or severe pain, occurring in the presence of well-established baseline pain. Breakthrough pain was further characterized as rapid in onset (within 3 minutes) and of short duration (median 30 minutes). Although the term "breakthrough pain" was used and understood by cancer specialists and was recognized as a clinical problem prior to this formal definition, Portenoy and Hagen's seminal paper paved the way for the systematic study of breakthrough pain. In a 2002 publication,[20] the American Pain Society defined breakthrough pain as:

"Intermittent exacerbations of pain that can occur spontaneously or in relation to specific activity; pain that increases above the level of pain addressed by the ongoing analgesic; includes incident pain and end-of-dose failure."

Figure 2. Representation of persistent and breakthrough pain.

The pathophysiology of breakthrough pain may be visceral, somatic, or neuropathic. When breakthrough pain is due to movement, whether voluntary or involuntary, it is referred to as "incident" pain. As with chronic pain, the etiology of breakthrough pain in cancer patients may be due to tumor progression or cancer treatment, or it may be unrelated to the cancer.[18] Breakthrough pain may occur as the result of inadequate ATC dosing (referred to as end-of-dose failure) or may be idiopathic and be unrelated to activity or dosing schedule.

Rescue medication for breakthrough pain should be individualized and titrated to achieve a balance between adequate analgesia and acceptable side effects. Traditionally, breakthrough pain was treated by the use of supplemental opioids.[6] However, before the availability of oral formulations, opioids for breakthrough pain were administered via the intramuscular route.[19] Today, breakthrough pain is primarily managed with short-acting oral immediate-release or transmucosal opioids, given as needed.[3,13,18,19,26] It has been standard practice to use the same opioid for the treatment of baseline and breakthrough pain, but in different formulations, such as long-acting morphine for baseline pain and short-acting morphine for breakthrough pain. However, with the availability of newer agents, it is now possible for different opioids to be used for ATC dosing vs breakthrough pain.[18,19] This approach may even be desirable as it potentially allows for the administration of lower doses of each agent, which may minimize dose-dependent side effects. Another strategy often used is the prophylactic treatment of breakthrough pain using higher dosages of ATC opioids maintained at all times; however, this strategy is not advisable because unacceptable side effects may result in some patients.[18]

Despite their wide use, the opioids used for breakthrough pain in cancer, such as morphine, hydromorphone, and oxycodone, are not very lipophilic, and therefore oral or sublingual formulations of these agents are poorly absorbed.[19] Their poor absorption may delay the onset of analgesia, and therefore not coincide with the rapid onset of breakthrough pain, making them largely ineffective in managing breakthrough pain.

By contrast, the rapid-onset opioid formulations are becoming more widely used. OTFC delivers fentanyl embedded in a sweetened matrix, which dissolves in the mouth. Because of its high lipid solubility, fentanyl is rapidly absorbed through the buccal mucosa, resulting in the rapid onset of pain relief. Although only part of the fentanyl dose is absorbed, the concentration absorbed is sufficient to exert its analgesic effect.[27] Indeed, in clinical studies, OTFC was found to be more effective than patients' usual opioid formulation for breakthrough pain, including morphine sulfate immediate release (MSIR). In a double-blind, randomized, multiple crossover study comparing OTFC with MSIR, 69% of patients found a successful dose of OTFC, and OTFC yielded outcomes (pain intensity, pain intensity differences, and pain relief) that were significantly better than MSIR.[28] The most common drug-associated side effects reported were somnolence, nausea, constipation, and dizziness. In a long-term safety study of OTFC in ambulatory cancer patients, no additional side effects were observed.[29]

Another rapidly acting formulation currently in development delivers morphine via the intranasal route. However, striking a balance between efficacy and local side effects can be challenging.[30] One nasal morphine formulation uses chitosan, a highly purified polysaccharide that has bioadhesive properties; in theory, by increasing the residence time of morphine on the nasal mucosa surface, morphine bioavailability may be improved.[31,32] The formulation is rapidly absorbed, with a maximal time to peak plasma concentration of [32] In a small trial with 14 patients, it was well-tolerated, and pain relief was recorded in as early as 5 minutes.[31] The use of intranasal fentanyl in 12 cancer patients with breakthrough pain also showed rapid relief, with 7 reporting reductions in pain scores after 10 minutes.[33] Larger, longer-term trials are necessary to fully evaluate the efficacy of these and other nasal formulations in patients with chronic cancer pain.

Breakthrough Pain in Patients With Chronic Noncancer Pain

Opioid use has been shown to be effective in the management of severe chronic noncancer pain due to a variety of causes, as highlighted in several consensus statements and guidelines issued by professional organizations and pain experts.

The pharmacologic management of chronic noncancer pain is based upon the principles and practices of treating chronic pain in cancer patients. Using an analgesic ladder approach, treatment is tailored to the individual patient and the intensity of pain. Opioids are used in combination with nonopioid analgesics for moderate to severe pain, and are used alone on a fixed schedule for chronic pain. For breakthrough pain, a short-acting opioid is used as needed. The American Pain Society has published guidelines for the management of acute and chronic pain associated with sickle cell disease and arthritis.[20,34]

In many patients with arthritis who are on medication to control chronic pain, a period of increased, episodic pain is experienced, and is often not adequately controlled by analgesic and/or anti-inflammatory therapy. Because of the severity of the pain and the adverse effects associated with higher doses of NSAIDs, other agents such as opioids are recommended. According to the American Pain Society guidelines,[20] the use of pure opioids such as oxycodone, morphine, and fentanyl is strongly recommended for the treatment of severe arthritis pain not relieved by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors and nonspecific NSAIDs. In patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, opioids should be used when other medications and nonpharmacologic interventions have been unsuccessful in providing relief of pain.[5,20] Studies in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis patients have shown that opioids (except codeine and propoxyphene), combined with NSAIDs, are effective in the treatment of moderate to severe pain. The weak opioid tramadol has been shown to be an effective treatment of breakthrough pain in osteoarthritis patients,[35] suggesting that other short-acting opioids may be useful as well.

Pain associated with sickle cell disease ranges from acute to chronic. However, it can be difficult to distinguish between the two since acute pain, which is common, not only varies in frequency and intensity but also can be persistent and recurrent. Frequently, recurring episodes of acute pain have the characteristics of chronic pain. Although chronic pain in sickle cell disease can last from 3 to14 days, many patients are pain free between these periods. In addition, a chronic pain syndrome is recognized in some patients with sickle cell disease in which pain increases over several days, peaks, and then declines to a baseline level.[36,37]

According to the American Pain Society guidelines for the treatment of acute and chronic pain in sickle cell disease,[34] an opioid together with an NSAID is recommended for mild-to-moderate pain. For moderate-to-severe pain, an opioid alone or in combination with an NSAID should be used. The type of opioid should be chosen based on the characteristics of the pain. For pain of short duration, a short-acting opioid is appropriate; for pain of long duration, a sustained-release opioid formulation should be used. A short-acting opioid may also be used as a rescue drug for breakthrough pain.

Research into the use of opioids for the management of chronic and breakthrough pain in noncancer patients continues to expand. Weak opioids and short-acting opioids may prove effective for treating severe acute or chronic pain in various patient populations, such as patients with migraine headaches and opioid-sensitive neuropathic pain.[38] Such pain is generally of rapid onset, so the use of short-acting agents in these settings may prove beneficial.

Potential Abuse of Opioids

The single-most cited concern regarding the therapeutic use of opioids for chronic pain is their potential for abuse, a concern underscored by the classification of opioids as scheduled narcotics. This concern is justifiable, as prescription opioid abuse is 5-fold higher today than it was in the 1980s. Drug abuse and diversion are not only societal problems, but also medical problems that need to be addressed. Although the prescribing of opioids is generally more accepted for chronic cancer pain, it should not be assumed that the rate of abuse in cancer (or noncancer) patients is lower than that in the general population. As is true for all patients with chronic pain, a history of substance abuse is a risk factor for cancer patients, and therefore oncologists must be vigilant when using opioids to manage chronic pain.

The stigma associated with opioid therapy for patients, families, and physicians alike stems from societal-driven perceptions and perhaps also from the ignorance of the pharmacotherapeutic basis of opioids for relieving pain. Also contributing to the perceived riskiness of prescribing opioids and consequent undertreatment is the confusion surrounding the terms of physical dependence, tolerance, addiction, and pseudoaddiction. Nevertheless, it is critical that the clinician treating patients with chronic pain be aware that opioid abuse is potentially a problem in every patient. A clear understanding of the characteristics and subtleties of physical dependence, tolerance, increased pain as a withdrawal symptom, pseudoaddiction, and addiction is imperative so that true addiction in the clinical setting can be recognized early and treated immediately.

Physical dependency and tolerance are biological phenomena and do not indicate addiction. Tolerance refers to the loss of therapeutic effect with continued use of a drug, and presumably involves changes at the receptor level.[39,40] The attenuation or loss of analgesic efficacy due to tolerance certainly complicates the treatment of chronic pain with opioids; however, the possibly eventual need to increase dose to reproduce the initial effects of an opioid should not be a reason for wholesale avoidance of the use of opioids in the chronic pain setting. Worsening pain in a patient receiving a stable dose of opioids should not be attributed to tolerance, but should be assessed as presumptive evidence of disease progression or even increasing psychological distress.[13]

Physical dependence reflects a state of neurophysiologic adaptation at both peripheral and central neurons,[41] and refers to the emergence of withdrawal symptoms following the abrupt dose reduction or cessation of administration of an antagonist. Although physical dependence is an expected consequence of the long-term use of opioids, it is not known what dose or dose ranges and duration of administration produce clinically significant physical dependence. Note that psychological dependence is distinguished from physical dependence, and, unlike physical dependence, psychological dependence is a component of addictive behavior.

Addiction is a psychological and behavioral syndrome that is manifested as a constellation of maladaptive behaviors, including craving, compulsive drug-seeking behaviors, and compulsive drug use.[39,40] The psychological dependency component of addiction refers to ideation about a drug and an intense desire to obtain the drug. Continual or increasing use of a drug despite negative physical, psychological, or social consequences defines addictive behavior. The opioid addict exhibits preoccupation with opioid use despite adequate pain relief, as well as uncontrolled continued use of opioids despite apparent adverse consequences associated with their use.

In general, opioids that are targeted for abuse are short-acting and potent agents such as oxycodone and hydrocodone. The "high" that the addict seeks is directly related to the rate at which the drug is absorbed. Despite the newly developed controlled-release formulations of these agents, addicts destroy the controlled-release mechanism, which normally provides a slow rate of absorption over an extended time period, to yield a sufficient amount of drug necessary to achieve the "high." Indeed, drug abuse and diversion with the short-acting agent oxycodone has been widely publicized. However, while addicts prefer short-acting drugs and even alter delivery systems of long-acting ones, the degree to which short- vs long-acting drugs is related to aberrant behaviors and abuse in patients with pain remains unknown.

Aberrant drug-related behaviors in the clinical setting may be extreme (eg, injection of an oral formulation), and therefore obviously indicative of addiction. However, not all drug-related aberrant behavior is indicative of addiction. Some apparently abnormal drug-related behaviors may reflect impulsive behavior driven by unrelieved pain or mental confusion about drug consumption. Pseudoaddiction is a term introduced in the cancer pain setting to refer to the apparent drug-seeking behavior in patients who have severe unrelieved pain and who have not received effective pain therapy.[42] Such behavior disappears when adequate analgesic treatment, including increased opioid dosing, is given. "Pseudoaddicts" may appear to be preoccupied with obtaining opioids, but unlike the addict, this preoccupation reflects a need for pain control. Pseudoaddiction can be distinguished from true addiction by observing that when pain is effectively controlled, either with opioids or through other means, the patient uses medications as prescribed.

Conclusions

A comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach that includes pharmacotherapy can lead to effective pain management in patients with moderate to severe chronic pain and breakthrough pain. Although there is little controversy regarding the therapeutic efficacy of opioids for the control of chronic pain in the cancer and noncancer patient, the necessary consideration of and knowledge about the risk of opioid addiction make patient management especially challenging. The legitimate concern about increasing the dose of opioids in patients with breakthrough pain should not translate into fear or uniform refusal to increase opioid doses. As outlined in several clinical practice guidelines, patient monitoring and continual reassessment are key to preventing psychological dependency and addiction while ensuring adequate relief of pain.

Data are beginning to accumulate demonstrating the effective use of opioids for the relief of severe chronic pain, including breakthrough pain, in noncancer patients, which will allow this therapeutic modality to gain greater acceptance by clinicians. The judicious use of opioids in select patients with severe chronic noncancer pain as an integral part of quality medical care is advocated by many professional organizations. The use of opioids is truly a "balancing act," but, as these drugs may be the most effective or only option for treating pain, avoiding or withholding their use because of the potential for abuse and diversion may result in ineffective pain management and unnecessary patient suffering.

References

- Loeser JD, Melzack R. Pain: an overview. Lancet. 1999;353:1607-1609. Abstract

- Wall PD, Melzack R. Textbook of Pain, fourth edition. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1999.

- Walsh D. Pharmacological management of cancer pain. Semin Oncol. 2000;27:45-63. Abstract

- Ashburn MA, Staats PS. Management of chronic pain. Lancet. 1999;353:1865-1869. Abstract

- Roth SH. A new role for opioids in the treatment of arthritis. Drugs. 2002;62:255-263. Abstract

- Portenoy RK, Hagen NA. Breakthrough pain: definition, prevalence and characteristics.

Routes of Opioid Administration

Opioids may be administered by several routes: oral, transmucosal, rectal, intravenous, subcutaneous, transdermal, and intraspinal (intrathecal and epidural). Individualized therapy should take into consideration several factors, including prior response to opioids and patient preference to route of administration. Initiating therapy with a short-acting oral agent is preferable, especially in the opioid-naive patient. Transitioning to a continuous-release agent, whether oral or transdermal, may easily be accomplished once tolerance to opioids is demonstrated.

Assessing the patient's response to several different oral opioids is recommended before switching to another route of administration. When changing drugs and not route of administration, comparisons must be made at equianalgesic doses. When changing route of administration and not drug, the dose of the drug must be adjusted; this is particularly important when switching between oral and parenteral routes if the opioid undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism.

Rectal administration is a safe, inexpensive, and effective route for delivery of opioids (and nonopioids) when a patient has nausea or vomiting or is otherwise unable to take medication by mouth or prefers another route. Transdermal (fentanyl) patches provide long-lasting analgesia (up to 72 hours) and typically are used for relatively stable analgesic requirements. Oral transmucosal fentanyl citrate (OTFC) is used for the relief of breakthrough pain primarily because of its rapid absorption and consequent rapid therapeutic effect (within 15 minutes).

Parenteral methods should be used only when simpler, less demanding, and less costly methods are inappropriate, ineffective, or unacceptable to the patient. This route may be useful if a patient cannot swallow and intravenous access is established. Intravenous administration provides a rapid onset of analgesia (within 2 to 10 minutes), but the duration of action may be shorter than with other routes. The subcutaneous route is as effective as the intravenous route, and may be more convenient in some situations, such as in home or hospice care. Because the bioavailability of opioids administered by a parenteral route (eg, morphine, hydromorphone, oxycodone, and codeine) is generally 2-3 times that of the oral route, when switching from the oral to the subcutaneous and intravenous routes, the dose must be decreased by one half or one third. Opioids administered parenterally may be given either intermittently (usually every 4 hours) or by continuous infusion.

In general, other routes of opioid administration are not recommended because they are either painful (ie, intramuscular) or are only useful in specific circumstances. For example, patient-controlled analgesia is used to determine an opioid dose when initiating therapy, and intraspinal administration of opioids (epidural or intrathecal) can be helpful in a very small select group of patients with intractable pain, such as those with bilateral or midline pain in the lower part of the body, or when systemic agents provoke intolerable side effects or inadequate pain relief.[10]

Because chronic pain of both cancer and noncancer etiology share the same neural mechanisms, treatment approaches may be extrapolated from the management of chronic cancer pain to pain of other causes. Based on the findings of several studies and reports demonstrating analgesic efficacy and acceptable side effects with opioid therapy in a wide range of chronic painful conditions (eg, osteoarthritis, sickle cell anemia, back pain, phantom limb pain, neuropathic pain, and headache), many professional organizations as well as expert groups in pain management, including the American Pain Society, now support the judicious use of opioids for selected patients with chronic noncancer pain.

Side Effects of Opioids

The more common side effects of opioids include constipation, nausea, sedation, and cognitive impairment (ie, confusion and delirium). When the cause of specific side effects is thought to be due to the accumulation of active metabolites, a switch to another opioid may mitigate the side effects.[10,13]

All patients on ATC opioid therapy need to be given laxatives prophylactically. Opioid-induced constipation is a frequent cause of chronic nausea and appears to be dose-related; it is characterized by large variability in individuals and is mediated by both central and peripheral mechanisms. Complete tolerance to this effect generally does not develop, and most patients require laxative/stool softener therapy for as long as they take opioids.[10,13]

By contrast, although nausea and vomiting is a common side effect of exposure to opioids, tolerance tends to develop, such that the effect usually disappears within the first weeks of treatment. Prophylactic use of an antiemetic is not necessary routinely, but an appropriate antiemetic is usually effective in limiting nausea and vomiting and should be used during the initiation phase of opioid therapy. In some patients, nausea and vomiting may persist beyond the opioid-initiation phase or occur de novo in patients on long-term opioid treatment and may become chronic in nature.[10,13]

Opioid-related central nervous system side effects include sedation, confusion and delirium, and myoclonus. Sedation and cognitive impairment commonly occur with the initiation of therapy or with dose escalation, but tolerance tends to develop to these effects, such that they usually disappear within the first week of treatment. In some patients, sedation and cognitive impairment may persist. Certain individuals may manifest a paradoxic stimulation with certain opioids, which may become attenuated with opioid rotation. Myoclonus, although common, is mild and infrequent; tolerance develops to this effect as well.[10,13]

Breakthrough Pain in Cancer Patients

In 1990, Portenoy and Hagen[6] proposed a standard definition of breakthrough pain in their prospective study of breakthrough pain in cancer patients. Breakthrough pain was defined as a transient increase in the intensity of moderate or severe pain, occurring in the presence of well-established baseline pain. Breakthrough pain was further characterized as rapid in onset (within 3 minutes) and of short duration (median 30 minutes). Although the term "breakthrough pain" was used and understood by cancer specialists and was recognized as a clinical problem prior to this formal definition, Portenoy and Hagen's seminal paper paved the way for the systematic study of breakthrough pain. In a 2002 publication,[20] the American Pain Society defined breakthrough pain as:

"Intermittent exacerbations of pain that can occur spontaneously or in relation to specific activity; pain that increases above the level of pain addressed by the ongoing analgesic; includes incident pain and end-of-dose failure."

Figure 2. Representation of persistent and breakthrough pain.

The pathophysiology of breakthrough pain may be visceral, somatic, or neuropathic. When breakthrough pain is due to movement, whether voluntary or involuntary, it is referred to as "incident" pain. As with chronic pain, the etiology of breakthrough pain in cancer patients may be due to tumor progression or cancer treatment, or it may be unrelated to the cancer.[18] Breakthrough pain may occur as the result of inadequate ATC dosing (referred to as end-of-dose failure) or may be idiopathic and be unrelated to activity or dosing schedule.

Rescue medication for breakthrough pain should be individualized and titrated to achieve a balance between adequate analgesia and acceptable side effects. Traditionally, breakthrough pain was treated by the use of supplemental opioids.[6] However, before the availability of oral formulations, opioids for breakthrough pain were administered via the intramuscular route.[19]

Today, breakthrough pain is primarily managed with short-acting oral immediate-release or transmucosal opioids, given as needed.[3,13,18,19,26] It has been standard practice to use the same opioid for the treatment of baseline and breakthrough pain, but in different formulations, such as long-acting morphine for baseline pain and short-acting morphine for breakthrough pain. However, with the availability of newer agents, it is now possible for different opioids to be used for ATC dosing vs breakthrough pain.[18,19] This approach may even be desirable as it potentially allows for the administration of lower doses of each agent, which may minimize dose-dependent side effects. Another strategy often used is the prophylactic treatment of breakthrough pain using higher dosages of ATC opioids maintained at all times; however, this strategy is not advisable because unacceptable side effects may result in some patients.[18]

Despite their wide use, the opioids used for breakthrough pain in cancer, such as morphine, hydromorphone, and oxycodone, are not very lipophilic, and therefore oral or sublingual formulations of these agents are poorly absorbed.[19] Their poor absorption may delay the onset of analgesia, and therefore not coincide with the rapid onset of breakthrough pain, making them largely ineffective in managing breakthrough pain.

By contrast, the rapid-onset opioid formulations are becoming more widely used. OTFC delivers fentanyl embedded in a sweetened matrix, which dissolves in the mouth. Because of its high lipid solubility, fentanyl is rapidly absorbed through the buccal mucosa, resulting in the rapid onset of pain relief. Although only part of the fentanyl dose is absorbed, the concentration absorbed is sufficient to exert its analgesic effect.[27] Indeed, in clinical studies, OTFC was found to be more effective than patients' usual opioid formulation for breakthrough pain, including morphine sulfate immediate release (MSIR). In a double-blind, randomized, multiple crossover study comparing OTFC with MSIR, 69% of patients found a successful dose of OTFC, and OTFC yielded outcomes (pain intensity, pain intensity differences, and pain relief) that were significantly better than MSIR.[28] The most common drug-associated side effects reported were somnolence, nausea, constipation, and dizziness. In a long-term safety study of OTFC in ambulatory cancer patients, no additional side effects were observed.[29]

Another rapidly acting formulation currently in development delivers morphine via the intranasal route. However, striking a balance between efficacy and local side effects can be challenging.[30] One nasal morphine formulation uses chitosan, a highly purified polysaccharide that has bioadhesive properties; in theory, by increasing the residence time of morphine on the nasal mucosa surface, morphine bioavailability may be improved.[31,32] The formulation is rapidly absorbed, with a maximal time to peak plasma concentration of

Breakthrough Pain in Patients With Chronic Noncancer Pain

Opioid use has been shown to be effective in the management of severe chronic noncancer pain due to a variety of causes, as highlighted in several consensus statements and guidelines issued by professional organizations and pain experts.

The pharmacologic management of chronic noncancer pain is based upon the principles and practices of treating chronic pain in cancer patients. Using an analgesic ladder approach, treatment is tailored to the individual patient and the intensity of pain.

Opioids are used in combination with nonopioid analgesics for moderate to severe pain, and are used alone on a fixed schedule for chronic pain. For breakthrough pain, a short-acting opioid is used as needed. The American Pain Society has published guidelines for the management of acute and chronic pain associated with sickle cell disease and arthritis.[20,34]

In many patients with arthritis who are on medication to control chronic pain, a period of increased, episodic pain is experienced, and is often not adequately controlled by analgesic and/or anti-inflammatory therapy. Because of the severity of the pain and the adverse effects associated with higher doses of NSAIDs, other agents such as opioids are recommended.

According to the American Pain Society guidelines,[20] the use of pure opioids such as oxycodone, morphine, and fentanyl is strongly recommended for the treatment of severe arthritis pain not relieved by cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) inhibitors and nonspecific NSAIDs. In patients with osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, opioids should be used when other medications and nonpharmacologic interventions have been unsuccessful in providing relief of pain.[5,20] Studies in osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis patients have shown that opioids (except codeine and propoxyphene), combined with NSAIDs, are effective in the treatment of moderate to severe pain. The weak opioid tramadol has been shown to be an effective treatment of breakthrough pain in osteoarthritis patients,[35] suggesting that other short-acting opioids may be useful as well.

Pain associated with sickle cell disease ranges from acute to chronic. However, it can be difficult to distinguish between the two since acute pain, which is common, not only varies in frequency and intensity but also can be persistent and recurrent. Frequently, recurring episodes of acute pain have the characteristics of chronic pain. Although chronic pain in sickle cell disease can last from 3 to14 days, many patients are pain free between these periods. In addition, a chronic pain syndrome is recognized in some patients with sickle cell disease in which pain increases over several days, peaks, and then declines to a baseline level.[36,37]

According to the American Pain Society guidelines for the treatment of acute and chronic pain in sickle cell disease,[34] an opioid together with an NSAID is recommended for mild-to-moderate pain. For moderate-to-severe pain, an opioid alone or in combination with an NSAID should be used. The type of opioid should be chosen based on the characteristics of the pain. For pain of short duration, a short-acting opioid is appropriate; for pain of long duration, a sustained-release opioid formulation should be used. A short-acting opioid may also be used as a rescue drug for breakthrough pain.

Research into the use of opioids for the management of chronic and breakthrough pain in noncancer patients continues to expand. Weak opioids and short-acting opioids may prove effective for treating severe acute or chronic pain in various patient populations, such as patients with migraine headaches and opioid-sensitive neuropathic pain.[38] Such pain is generally of rapid onset, so the use of short-acting agents in these settings may prove beneficial.

Potential Abuse of Opioids

The single-most cited concern regarding the therapeutic use of opioids for chronic pain is their potential for abuse, a concern underscored by the classification of opioids as scheduled narcotics. This concern is justifiable, as prescription opioid abuse is 5-fold higher today than it was in the 1980s. Drug abuse and diversion are not only societal problems, but also medical problems that need to be addressed. Although the prescribing of opioids is generally more accepted for chronic cancer pain, it should not be assumed that the rate of abuse in cancer (or noncancer) patients is lower than that in the general population. As is true for all patients with chronic pain, a history of substance abuse is a risk factor for cancer patients, and therefore oncologists must be vigilant when using opioids to manage chronic pain.

The stigma associated with opioid therapy for patients, families, and physicians alike stems from societal-driven perceptions and perhaps also from the ignorance of the pharmacotherapeutic basis of opioids for relieving pain. Also contributing to the perceived riskiness of prescribing opioids and consequent undertreatment is the confusion surrounding the terms of physical dependence, tolerance, addiction, and pseudoaddiction. Nevertheless, it is critical that the clinician treating patients with chronic pain be aware that opioid abuse is potentially a problem in every patient. A clear understanding of the characteristics and subtleties of physical dependence, tolerance, increased pain as a withdrawal symptom, pseudoaddiction, and addiction is imperative so that true addiction in the clinical setting can be recognized early and treated immediately.

Physical dependency and tolerance are biological phenomena and do not indicate addiction. Tolerance refers to the loss of therapeutic effect with continued use of a drug, and presumably involves changes at the receptor level.[39,40] The attenuation or loss of analgesic efficacy due to tolerance certainly complicates the treatment of chronic pain with opioids; however, the possibly eventual need to increase dose to reproduce the initial effects of an opioid should not be a reason for wholesale avoidance of the use of opioids in the chronic pain setting. Worsening pain in a patient receiving a stable dose of opioids should not be attributed to tolerance, but should be assessed as presumptive evidence of disease progression or even increasing psychological distress.[13]

Physical dependence reflects a state of neurophysiologic adaptation at both peripheral and central neurons,[41] and refers to the emergence of withdrawal symptoms following the abrupt dose reduction or cessation of administration of an antagonist. Although physical dependence is an expected consequence of the long-term use of opioids, it is not known what dose or dose ranges and duration of administration produce clinically significant physical dependence. Note that psychological dependence is distinguished from physical dependence, and, unlike physical dependence, psychological dependence is a component of addictive behavior.

Addiction is a psychological and behavioral syndrome that is manifested as a constellation of maladaptive behaviors, including craving, compulsive drug-seeking behaviors, and compulsive drug use.[39,40] The psychological dependency component of addiction refers to ideation about a drug and an intense desire to obtain the drug. Continual or increasing use of a drug despite negative physical, psychological, or social consequences defines addictive behavior. The opioid addict exhibits preoccupation with opioid use despite adequate pain relief, as well as uncontrolled continued use of opioids despite apparent adverse consequences associated with their use.

In general, opioids that are targeted for abuse are short-acting and potent agents such as oxycodone and hydrocodone. The "high" that the addict seeks is directly related to the rate at which the drug is absorbed. Despite the newly developed controlled-release formulations of these agents, addicts destroy the controlled-release mechanism, which normally provides a slow rate of absorption over an extended time period, to yield a sufficient amount of drug necessary to achieve the "high." Indeed, drug abuse and diversion with the short-acting agent oxycodone has been widely publicized. However, while addicts prefer short-acting drugs and even alter delivery systems of long-acting ones, the degree to which short- vs long-acting drugs is related to aberrant behaviors and abuse in patients with pain remains unknown.

Aberrant drug-related behaviors in the clinical setting may be extreme (eg, injection of an oral formulation), and therefore obviously indicative of addiction. However, not all drug-related aberrant behavior is indicative of addiction. Some apparently abnormal drug-related behaviors may reflect impulsive behavior driven by unrelieved pain or mental confusion about drug consumption. Pseudoaddiction is a term introduced in the cancer pain setting to refer to the apparent drug-seeking behavior in patients who have severe unrelieved pain and who have not received effective pain therapy.[42] Such behavior disappears when adequate analgesic treatment, including increased opioid dosing, is given. "Pseudoaddicts" may appear to be preoccupied with obtaining opioids, but unlike the addict, this preoccupation reflects a need for pain control. Pseudoaddiction can be distinguished from true addiction by observing that when pain is effectively controlled, either with opioids or through other means, the patient uses medications as prescribed.

Conclusions

A comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach that includes pharmacotherapy can lead to effective pain management in patients with moderate to severe chronic pain and breakthrough pain. Although there is little controversy regarding the therapeutic efficacy of opioids for the control of chronic pain in the cancer and noncancer patient, the necessary consideration of and knowledge about the risk of opioid addiction make patient management especially challenging. The legitimate concern about increasing the dose of opioids in patients with breakthrough pain should not translate into fear or uniform refusal to increase opioid doses. As outlined in several clinical practice guidelines, patient monitoring and continual reassessment are key to preventing psychological dependency and addiction while ensuring adequate relief of pain.

Data are beginning to accumulate demonstrating the effective use of opioids for the relief of severe chronic pain, including breakthrough pain, in noncancer patients, which will allow this therapeutic modality to gain greater acceptance by clinicians. The judicious use of opioids in select patients with severe chronic noncancer pain as an integral part of quality medical care is advocated by many professional organizations. The use of opioids is truly a "balancing act," but, as these drugs may be the most effective or only option for treating pain, avoiding or withholding their use because of the potential for abuse and diversion may result in ineffective pain management and unnecessary patient suffering.